Terroir

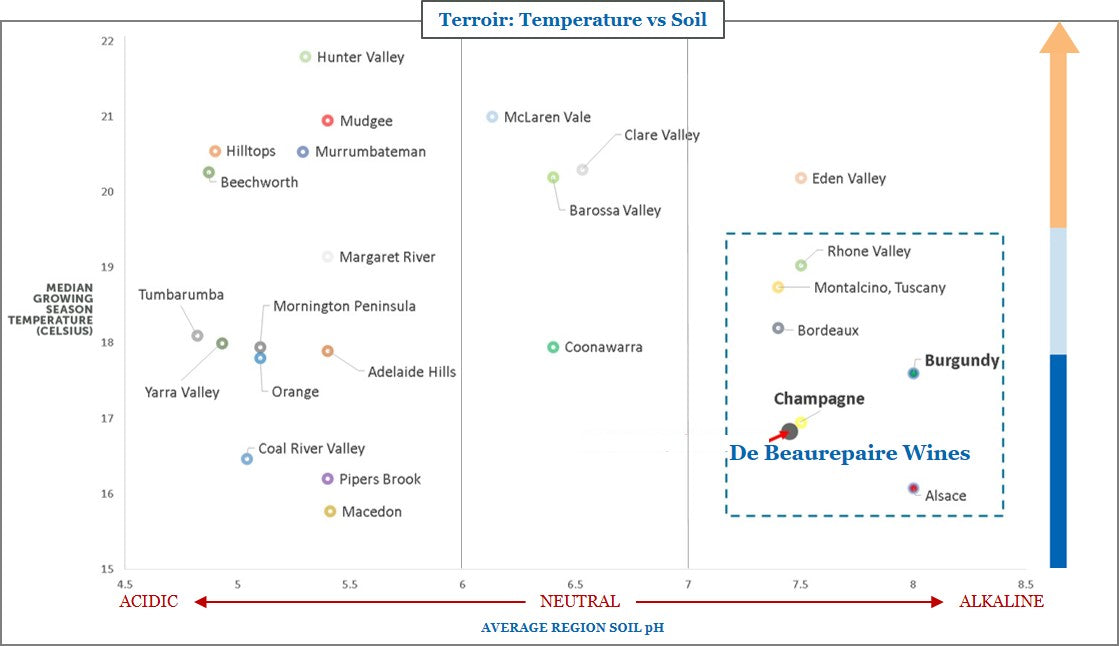

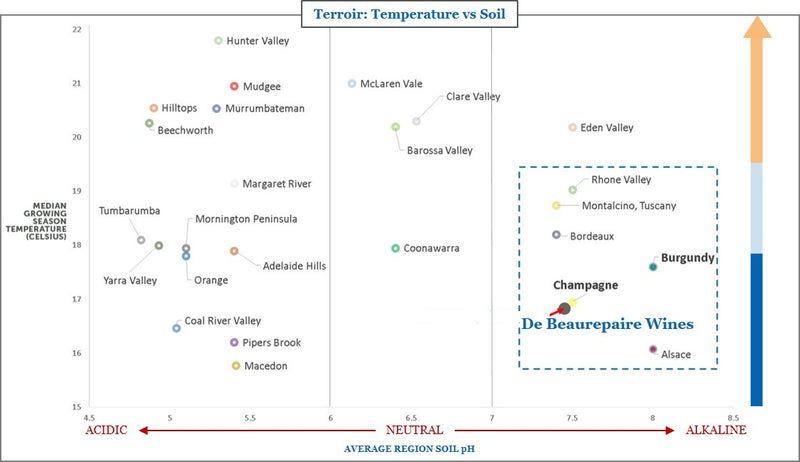

Great wine is made in the vineyard, and it all starts with terroir. Our exceptional terroir is the closest comparable in Australia to Burgundy in France.

Much is written about the qualitative aspects of terroir – the culture, knowledge and techniques used at a specific vineyard location. Some of these are understandable when you speak with French vignerons who have hundreds of years of growing notes covering most seasons they will experience. However, we set our sights on more quantitative measures that define the great regions of France and in particular, the great vineyards of Burgundy, upon which we could develop our own cultural aspects of terroir.

The key quantitative factors are soil, climate, and location, all of which are inter-related - if just one or two, then why are the best vineyards of Burgundy constrained to a narrow 1km wide by 60 km strip of land?

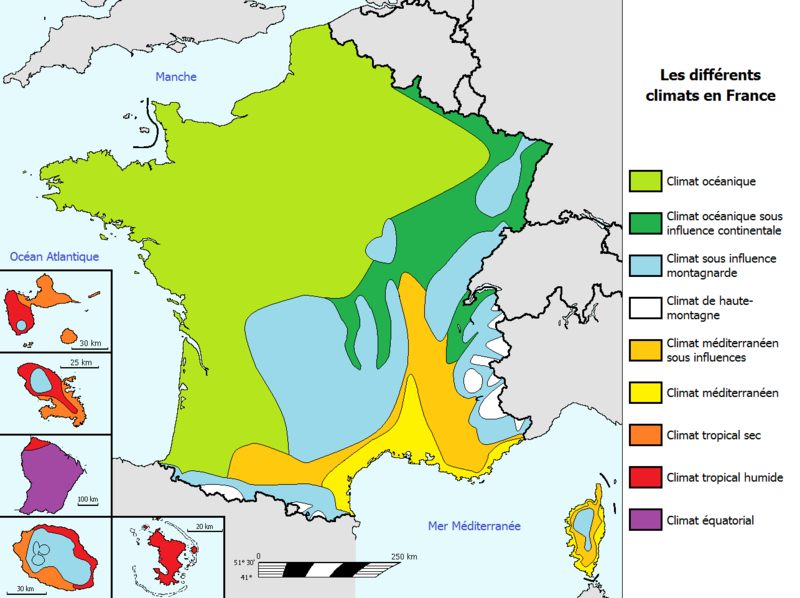

Burgundy is nearly 400 kilometres from either the Mediterranean, Atlantic or Channel producing a continental climate with cool nights which helps retain flavour and aroma and warm days to ripen the grapes.

Burgundy's best vineyards lie on shallow (mid-slope) sandy-loam soils that have been enriched with limestone making them mildly alkaline (pH 7.5 to 8).

With these parameters in mind, we conducted an extensive search in the 1990s encompassing most of the major wine regions of South East Australia. However, due to the lack of all 3 key Burgundian ingredients across these established wine regions – a very cool, inland climate with shallow sandy-loam soils on limestone - we realised the need to pioneer a new wine region.

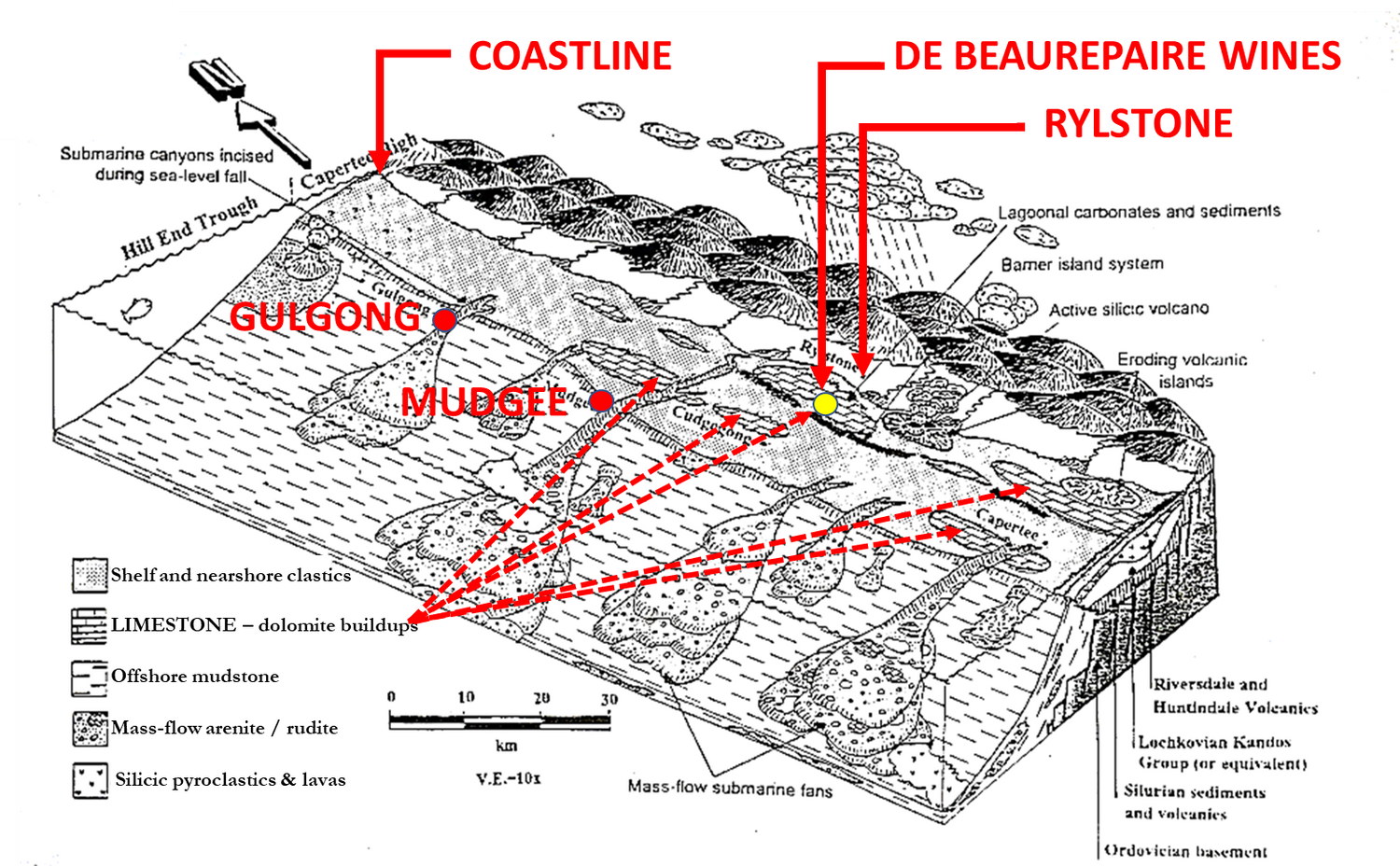

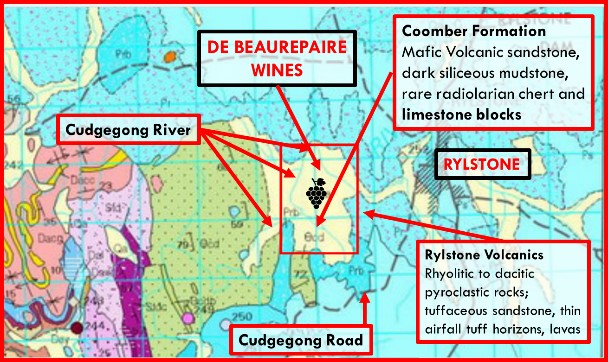

During the process we found a shallow valley with a narrow limestone band less than 1 kilometre wide, to the west of Rylstone, a small high elevation village on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range. Remarkably this valley provided all the key ingredients.

Famous for fine wool production, Rylstone is located 40 kilometres south-east of Mudgee (and nominally within Mudgee’s Geographic Identification zone, but with vastly different climate and soil type). Our vineyard has what we believe are unique conditions for Australia, conditions which make it arguably the closest ‘terroir’ in Australia to Burgundy.

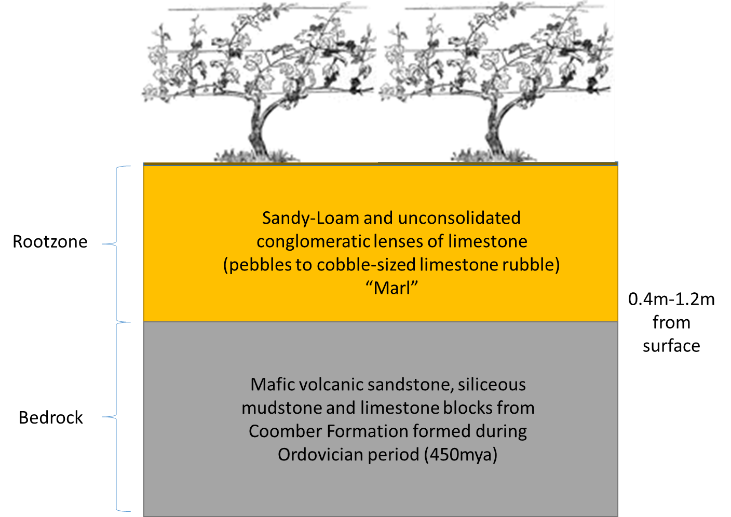

The formation story of our terroir commenced approximately 400 million years ago during the Ordovician era, a time when the seas were rich with ammonoid molluscs (shellfish). At this time, Australia was the most eastern portion of Gondwana and rested across the equator with warm coastal waters, coral reefs and bountiful sealife. Over the next 400 million years, the shellfish which inhabited these reefs and coastlines were compressed into very high-grade strip of limestone running along the western edge of the Great Dividing Range - which you see at the nearby Jenolan Caves.

Our vineyard resides upon one of these ancient coral reefs. The limestone, which extends under our vines, was mined just south of our vineyard for the nearby Kandos Cement Works to make the cement which built the Sydney Harbour Bridge and much of Sydney during the 20th Century.

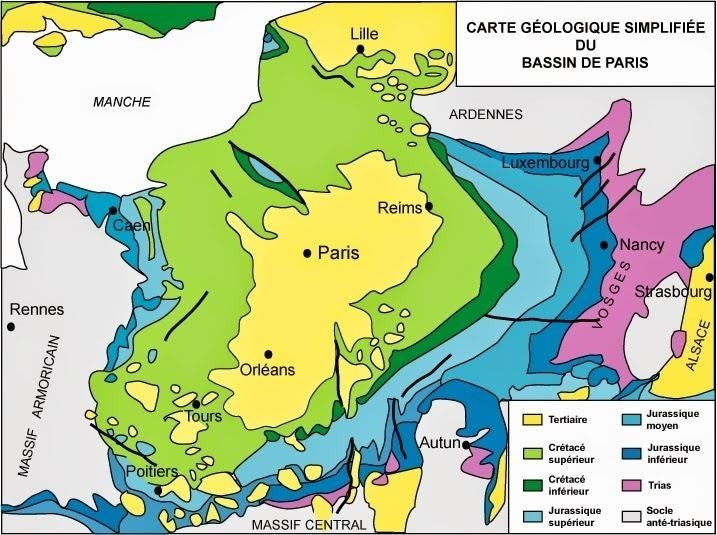

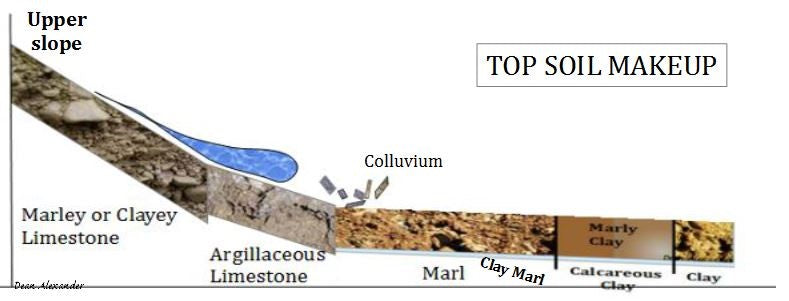

Approximately, 150 million years ago, during the Jurassic period (Mesozoic era) as the great super continent of Pangea was fracturing and water started to cover the rift valley between Europe and North America, the coastline of France was a long way inland from its current location. This coastline traced a course from the cliffs of Dover around Champagne, through Burgundy and then roughly towards what is now the Atlantic Coast through the Loire Valley. At the same time, the climate of France was closer to current day Miami. These shallows seas covering north west and south west France were teeming with aquatic life with shorelines rich with shellfish and waters filled with Plankton. These plankton and shellfish deposited into layers of calcareous sedimentation. Over the millions of years the plankton converted into the chalk of Champagne and the shellfish metamorphosed into thin, elongated deposits of limestone tracing the old shoreline (parts of which are called the Kimmeridgian chain). These limestone deposits, driven upwards into scarps by faulting at the time the Alps formed and mixed up with clay and sand into marl, form the basis of the different Burgundian wine regions from Chablis in the far north, through the Côte d’Or (Côte de Nuits, Côte de Beaune) down to Maconais. The premium vineyards of Burgundy closely hug these narrow soil profiles. Hence the Côte d’Or vineyard planting region is 65 kilometres long by only 1.5 kilometres wide. In much of Burgundy there is no limestone in the soil - and no vineyards planted.

The different geological structures of the Rylstone region are most evident by the volcanic rock (Rylstone Volcanics) overlaying much of the limestone (Coomber formation) which appear in isolated locations where the lava flows ceased, or the volcanic rock has been eroded. Due to the hardness of the volcanic rock, it tends to form the highpoints around the area. The boundaries of the two rock types are very clearly defined.

Our vineyard closely hugs the narrow (1km wide) limestone formation which runs in a relatively north-south trend just west of Rylstone and our plantings stop wherever the soils turned to volcanic rock. The driveway down into the vineyard has volcanic soils on the eastern side (Rylstone/Kandos town side) which have been left as pasture, and limestone infused soils on the western side sloping down to the River which have been planted with vines.

Volcanic rock is incredibly hard and acidic, making fracturing for root growth difficult and the acidity makes the soil micro-organisms less efficient, meaning they require more soil to produce the same mineral availability for the vines. It is for this reason that limestone infused soils with their high pH (and mild alkalinity) can be vastly shallower. In fact, some of the best vineyard soil in France can be as shallow as 30cm in the Côte de Blancs in Champange (where many of the best Blanc de Blancs Champagnes are found), or less than 50cm on the Grand Cru midslopes of Burgundy.

Cistercian and Cluniac monks figured out that different soil types and locations could dramatically influence a wine’s character. They subsequently divided vineyards into some 1,463 patches surrounded by rock walls, known as “climats”. Variations in soil are broadly categorised as physical and chemical. Physical differences in soils such as depth, layering, consistency, water retention, coarseness and structure all impact on the growth habit and resultant fruit of the vine. Chemical differences are perhaps more subtle, and include acidity (and alkalinity), macronutrient availability, micronutrient availability, chelation and soils microflora. These two elements are deeply interconnected and manifest as an endless variety of nuance and variation in grape, must and wine flavours. The best vineyards in Burgundy (e.g. Romanee-Conti) are situated on the mid-slope where erosion keeps the soil relatively shallow, but there is more top soil than the higher slope areas where erosion exposes the limestone in spots.

Our vineyard soils are relatively shallow, ranging from less than 20cm with limetone poking through at the southern end to over a metre depending on the pooling of soil from erosion (Colluvium/Slope Wash) from the slopes above. There is much variance, as to be expected from a 55-hectare vineyard which covers 1.5km of rolling hills and then up a slope, but the result can be very shallow root zones and, depending on the exact soil composition, very good drainage reducing the availability of water. This reduces vine vigour and concentrates the grapes - improving grape colour and flavour intensity. With experience, we have gradually reshaped parts of our vineyard to their most appropriate varieties. Our Cabernet is planted on the deepest soils, which they love, where slope wash has pooled over the millenia. Whereas our Chardonnay is planted on the shallowest soils in the vineyard. We are 500 years behind Burgundy where the Cistercian and Cluniac monks figured out all the soil types beneath much of vineyard from centuries of meticulous record keeping, but with the help of science, we are hopeful that we may get a handle on it within 50 years.

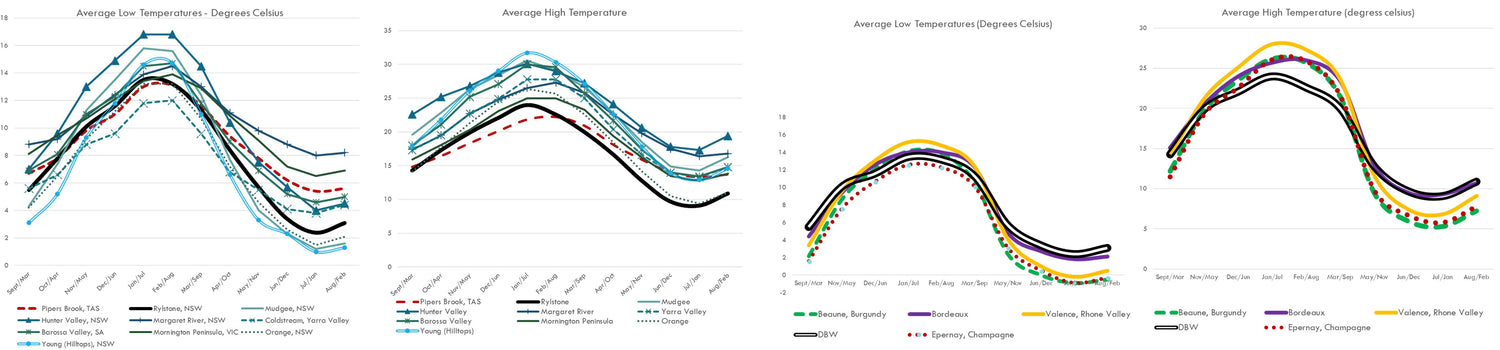

Climate is the final piece of the terroir puzzle. It is an important piece, but less so than soil and geology. There are many valleys in Burgundy sharing the same temperature and inland location, but only one Côte d’Or. Climate drives elements of the vine’s growth and grape ripening which are largely determined by Sunshine, Aspect, Heat Summation, Rainfall, Humidity, Wind and Diurnal patterns (daily temperature variation). Every vineyard location in the world is unique and on a micro-climate level there can be great variations – we have watched storms cross parts of the vineyard soaking them and leaving other areas dry, and we also have areas where cold air pools and where there is higher exposure to wind.

Starting at the top, there are two major climate types – continental and maritime. Maritime climates are well regulated by the ocean and experience very minor changes in temperature, regardless of location and season. Continental climates are inland and lack the temperature regulation, producing wild swings in daily temperature.

In terms of viticulture, large daily temperature ranges (diurnal variation) is a major source of stress for vines. Much like any living organism, moving quickly from cold to hot, or even cool to warm, results in a response – in humans we put on and take off clothing layers. In grape vines, the stress makes them look to protect their offspring, their seeds, and in turn results in a thickening of the grape skins. Grape skins are where most of what we call ‘terroir’ is expressed. A good example of their importance is the difference between a red wine and a rosé wine and the use of skins in winemaking.

Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are naturally very thin skinned varieties. This means that when grown in climate with large diurnal variation, i.e. continental, the skins thicken which can produce increased structure and intensity. It is for this reason that Burgundy and Champagne, with their continental climates, focus on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay; whereas Bordeaux with its maritime climate grows thicker skinned varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, and not the other way around.

Cool nights also protect the grape's fragile perfumes and flavours, whilst the warm days ripen the fruit ensuring a more balanced grape for better winemaking.

Rylstone is located on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range, ~160 kilometres from the coast. The natural wind direction is also from the west, i.e. further inland making them dry. Temperatures can easily change 25 to 30 degrees in a day and the dry inland winds reduce humidity, and therefore some disease risk. The coolest temperature we have recorded is minus 14 degrees. Our location west of Rylstone is also in a rain shadow driven by the large water mass of Lake Windamere to our West which breaks up storm fronts and as we’re on a rising slope toward the peak of Mt Coomber Melon with two large valleys starting either side, the wet weather is directed to the north down the Bylong Valley and to the south down Capertee Valley.

We produce Burgundian/Champagne varieties and Bordeaux and Rhône Valley varieties. This was driven by an initial need over the past 20 years to sell large portion of our grape production to other wineries to provide cashflow to fund our own winemaking operations; and in the 1990s, there was a heavy focus on Bordeaux varieties (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Semillon) and Rhône varieties (Shiraz) across Australia – so we planted what was in demand. The net result has been some wonderful discoveries. With beautiful, textural and perfumed Cabernets; and smooth, long Shiraz pointing to the use of continental and maritime as a guide rather than a rule book for vineyard site and grape variety selection.

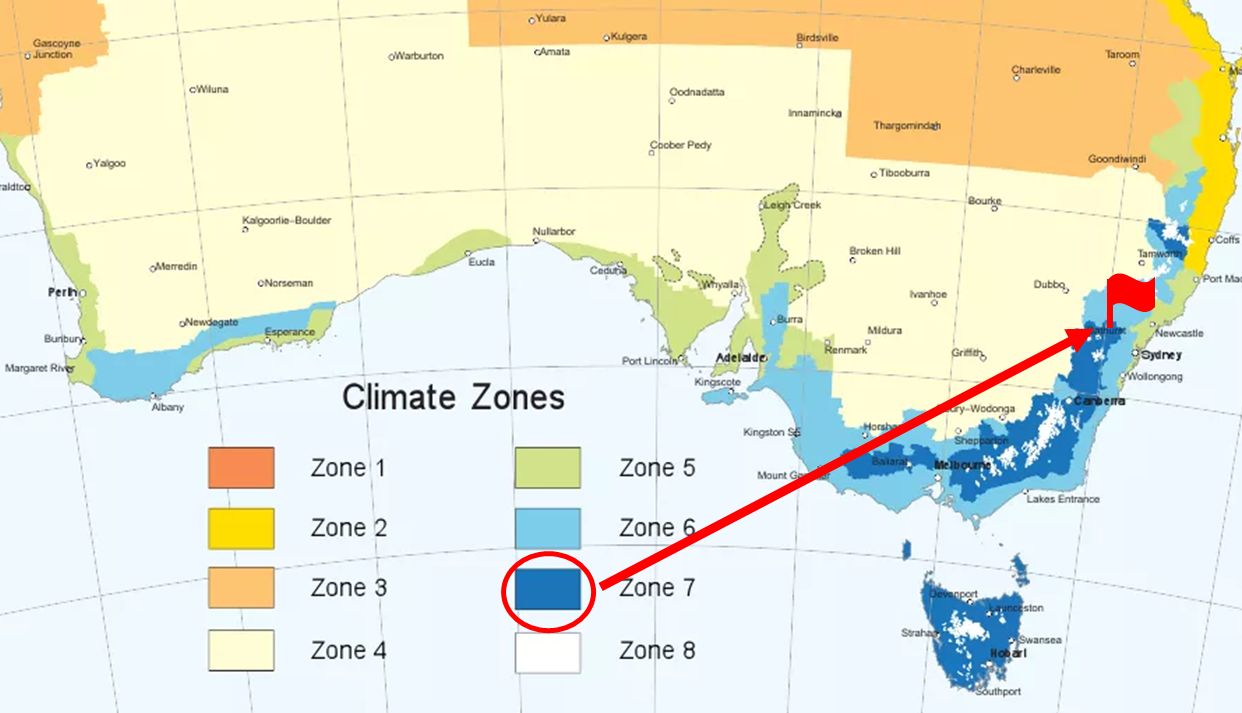

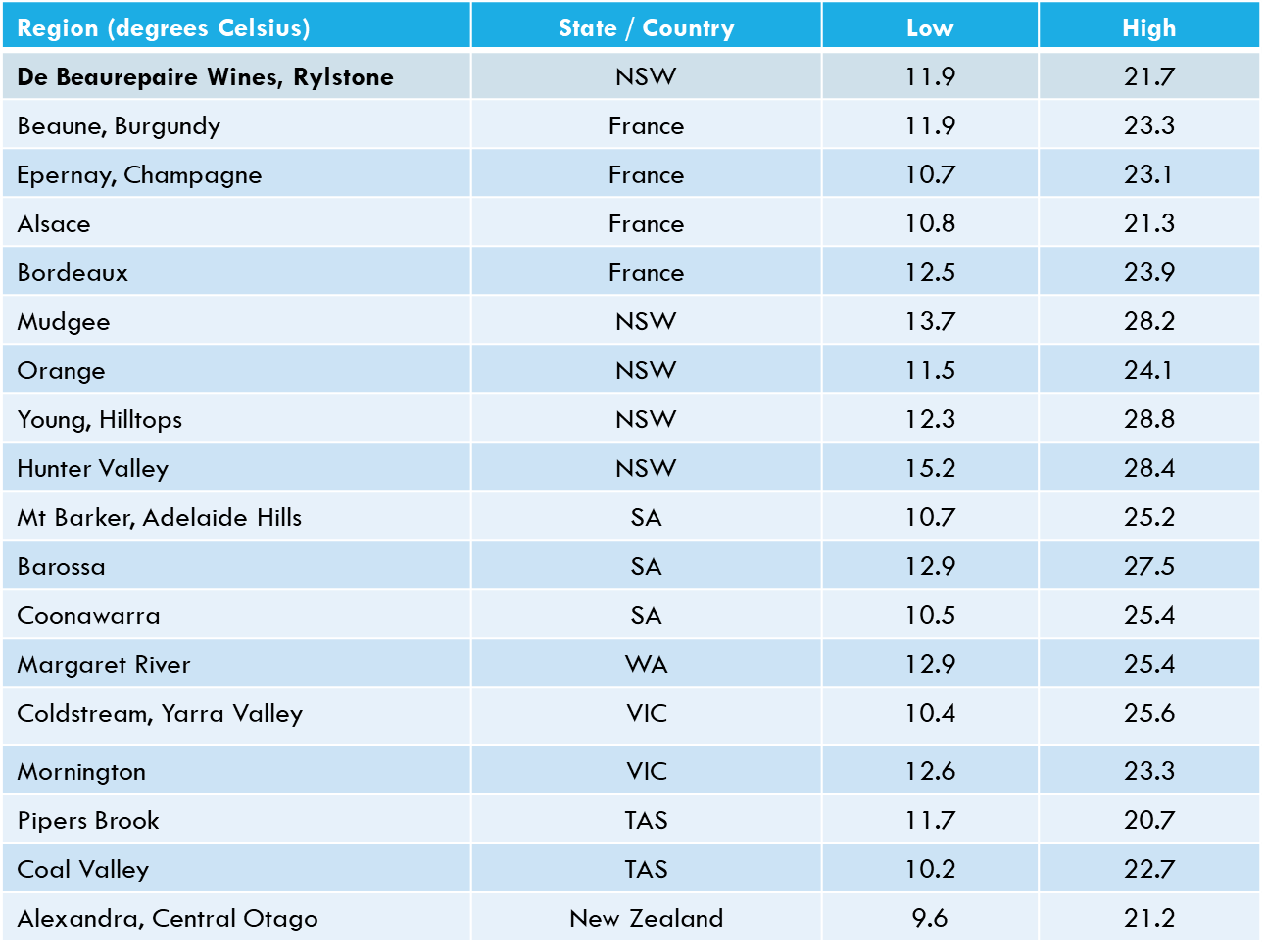

The altitude of our vineyard (600 to 650 metres) produces a very cool climate, accentuated by the sandy-loam on limestone soil structure which retains very little heat and makes us as cool as the higher elevations of Orange with its 'warmer' volcanic rocks or the southerly latitudes of Central Otago and Tasmania. Once the sun sets, all the day’s heat is quickly lost – and produces a vintage which is arguably one of the last on Mainland Australia, and more in line with Tasmania and Central Otago New Zealand. A later vintage means longer and slower grape ripening, which can result in better grape acid and sugar balance at harvest. Critically for us, the growing season temperatures of Rylstone are on average very close to Champagne and Burgundy.

The combination of soil structure, climate and temperature range for our 55-hectare vineyard makes it arguably one of the closest approximations of Burgundy in Australia. Whether that is Grand Cru Burgundy or Premiere Cru Burgundy, only time will tell. We will also endeavour to create our own terroir winemaking style, as evidenced by the trophies and awards we have won in non-Burgundy / Champagne varieties like our Botrytis Semillon, Cabernet-Merlots and Shiraz-Viogniers. As we continue to flesh out our understanding of our very unique terroir, we will continue to update this page as we believe, when it comes to winemaking, ‘terroir’ is all-important

Sources

Terroir chart: The points reflect the averages for each region, based on published sources. Individual wineries may differ from the average on either scale.

National Land & Water Resources Audit, 2004; Bureau of Meteorology; Assessing the pH and pH buffering capacity of Australian viticultural soils, Ben P. Thomas, Doug Reuter, Richard H. Merry and Ben Robinson